/International Roundtable about Performance art/

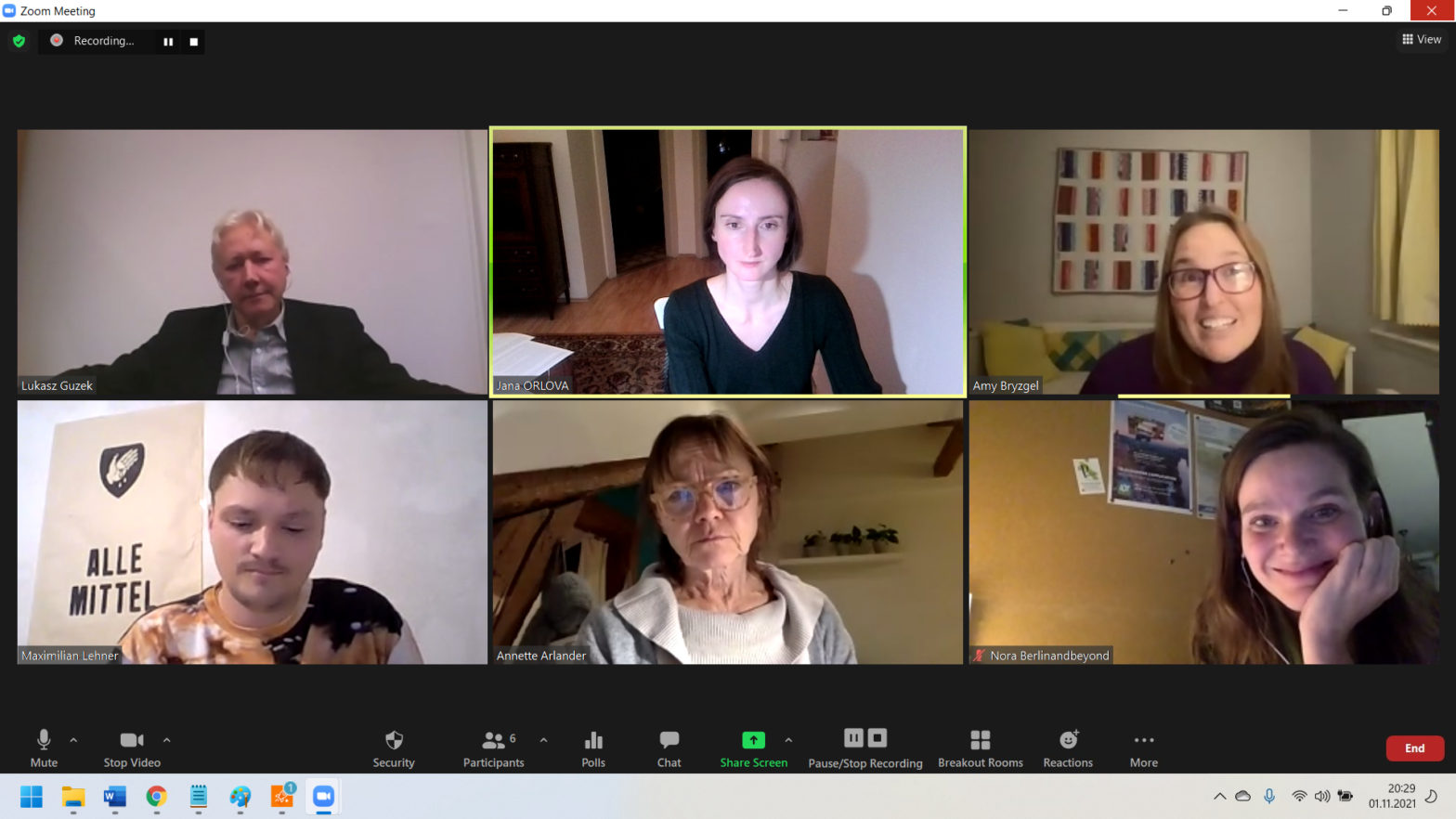

An international meeting of theorists, historians and curators of performance art took place on November 1st 2021 via the Zoom platform. The following attended the event (in alphabetical order): Annette Arlander (FI), Amy Bryzgel (UK), Łukasz Guzek (PL), Nora Haakh (DE), Maximilian Lehner (AT) and Jana Orlová (CZ), who was the organizer.

The round table has pointed out how diverse opinions about performance are, as well as the fact that many theorists and practitioners in the field have not yet asked many questions about the nature of performance or its differences from theater. Fine-arts historians such as Amy Bryzgel and Łukasz Guzek were crystal clear that performance art is part of the history of fine arts, while the views of those who are in contact with the theater scene or performance studies were much more cautious. The debate also showed the difference between „old school performance art” (Annette Arlander) and newer approaches. Different views have emerged on whether the performance can be delegated, whether the context is a sufficient distinguishing feature and whether it needs to be defined at all. Given that there were sometimes misunderstandings among the debaters caused by terminological deviations, the effort to find typical features of performance seems to be necessary for the further development of the field. There has also been a tendency to move performance art onto the stage, which is caused by artists and curators making pragmatic effort to use theater grants and funding (which is more generous) and by theaters to expand their repertoire. Suggestions have also been made regarding the methodology to be used when examining performance during the discussion.

(Photo: Facebook Verlag)

Theatre and dance versus performance art

Jana Orlová: Good afternoon, everyone. I am glad to see you here! Thank you for taking the time to participate in this event. Let me introduce myself briefly. I’m a researcher focusing on the difference between performance art and theatre and I’ve invited you as you are all well-known scholars in the field coming from different European countries.

I don’t want to talk much about my work, I’d rather discuss our shared points of interest. We come from different backgrounds, which I think is great. We can confront different points of view. We can start with the basic question: What is performance or performance art for you? I am using the term visual performance as well, which according to Claire Bishop means performance done by visual artists. I feel like we need this distinction, as performance art is a very broad term and it’s become really unclear over the last few years what we’re talking about when talking about performance. Hence this term “visual performance”. For example, in the Czech Republic the term performance is used for alternative theatre, partly as there’s a general trouble with the word performance for speakers who don’t have English as their mother language. Through my research I’ve come across with a lot of misunderstandings and misuse of the word. On the other hand, many theatre theorists claim visual performance to be part of theatre. Visual theorists are convinced that visual performance belongs to visual art… So to begin with, I’d like to know your opinions. What do performance, performance art and visual performance mean to you?

Amy Bryzgel: I think the line between experimental theatre and performance is quite thin. I mean, we have examples where performance (what we consider a visual performance) did come out of a sort of experimental theatre tradition. One example is Tadeusz Kantor in Poland, although he was a theatre director, but the performance art genre was refering to him, he was an influencer and also a source. Also, the Judson Church (Judson Dance Theatre) in New York, the New York scene isn’t really my area of specialisation, but it seems there was a lot happening at the same time in the sixties and seventies and it was all very mixed. I mean, there were people like Allan Kaprow who was a visual artist, but he was working with John Cage, who was a musician, and, you know, and then there were things going on at Judson Church, and I think they were all connected a little. So this historical line to me does seem a bit blurry in terms of experimental theatre and performance art.

Annette Arlander: I have to say, I am more of an artist than a scholar and I usually write about my own work. However, I spent many years as professor of performance art and theory in Helsinki (2001 – 2013) and it was within the context of the theatre academy. So it was my daily business to try to define the distinction between performance art and theatre, which was very exhausting. At some point I changed the name of the program to Live Art and Performance studies in order to make things easier in that context. So, I understand the need to define concepts, but I’ve come to feel that the meanings of some terms change over the years. For instance, toward the end of eighties Josette Feral speaks of performance art as a kind of experimental theatre or a less traditional theatre. Also Marvin Carlson did the same in his earlier writing. So it’s very confusing because it’s not the way those words are used today. But were I to mention a very good, almost caricature-like distinction between theatre and performance, that would be a text by Marilyn Arsem. She has written something like a manifesto for performance art for a festival in Venice 2011. She made a list of differences, like the use of real time as opposed to narrative time, the use of the artist’s own body as opposed to other people’s bodies, the use of risk taking and many other things. (Performance art is now, performance art is real, performance art requires risk, performance art is not an investment object, performance art is ephemeral.) Not all performance artists would agree with this of course, as they work in different ways, but I think it’s very useful. It can be found in the archive of the journal Total Art.

Orlová: In my case the need to distinguish comes also from my position as an artist confronted with the theatre scene. And I felt the urge to define what I’m doing and why it is not theatre. Because if it were theatre, it should be evaluated as theatre… But if you try to evaluate visual performance as theatre, it simply doesn’t work, because they work on different basis.

Nora Haakh: I think I have a lot in common here with other people as in I have a PhD., I’m an artist and a researcher, but I’m also working in the performing arts as a dramaturge. So as dramaturge especially I’m familiar with the processes of translating practice into descriptions that are necessary. Why? Because there are certain contexts in which labels are necessary, usually applying for funding or marketing a piece to fit into the programme or aesthetic vision of a certain platform and to present it to an audience. So what I’ve noticed there is, as you said, people doing stuff and they might call it performance, as it’s a term considered to be a more open thing My own practice that I sometimes describe as performance comes from a whole different field, the field of graphic recording, graphic facilitation of generative scribing in which basically live visualisation is used to harvest collective processes of brainstorming, and this can take place in collective creative processes in the arts, but also in pedagogical, political and also corporate contexts. There is this beautiful person called Kelvy Bird who has been developing an approach called Generative Scribing. I find it interesting that even though the practice could be very close, it is one example of fields not really in conversation with each other. So as a practicing Graphic Recorder, how I use live visualisation in performance includes bringing tools back from a context that is not primarily the artistic space into the artistic space via performance projects in which I participate.

(foto: Rolf Broberg)

Questions of authenticity

Orlová: I feel like it would be good to point out that in countries where English is not the first language there is often trouble with the term performance itself, because it is used very broadly and freely. It’s forgotten that performance is in general meaning some kind of action, and at the same time an output: in a sense the performance/ output of a manager or a car (how the car is quick and the manager productive). Generally, you can simply perform (do things) in everyday life too… we are performing at this very moment; however it is not an artistic performance. And in artistic performance, there’s a distinction between performing arts based on professionality, rehearsals and repetitions (i.e. theatre, dance, music) and performance art/visual performance. Visual performers are deskilled in performing arts and they don’t create pieces in terms of rehearsals and repetitions. Author reading is also a kind of artistic performance, which doesn’t belong in the performing arts. Maybe here we can start talking about the differences between visual performance and theatre…

Amy Bryzgel: I was just thinking about the importance of authenticity within performance art. I find it helpful with my students because they come to class thinking of the performing arts or performances that are repeated and rehearsed etc. And it’s not that performance art is never repeated because, of course, we know that performance artists will do things many times. But it’s perhaps more about the authenticity of expression. When you’re acting, you are trying to have an authentic expression too, but it’s not really meant to be your own. It’s the character, and I’m speaking very strict here. But I think it’s interesting if you look at someone like Marina Abramović because she’s done both. She’s done performance art and she’s done more theatrical type stuff, and it’s really her earlier work where I think you can see the authenticity, that I think is so important for performance art, whereas her later stuff I think is somewhere between theatre and performance art, and in my opinion, it’s just not as good.

(Photo: Shelby Lessig)

Orlová: I was thinking about authenticity a lot in my research, because a lot of researchers use authenticity to distinguish performance and theatre, saying that performance is authentic and theatre isn’t. However in the end I think this whole concept of authenticity is not satisfactory enough, as visual performance is not fully authentic either. And on the other hand, there can be authenticity in theatre too: within its fictional world. In the real-world authenticity usually arises when something unexpected happens (you are surprised, confused, or shocked). From my point of view, these are moments of real authenticity, we can call them “fragments of authenticity”. And indeed, in visual performance the range of authenticity is much broader than in theatre, because theatre is constituted by rehearsals and repetitions. That’s why there is not so much space for (fragmented) authenticity.

Arlander: I feel like authenticity is a theatrical term. Actors are always interested in seeming authentic. I’ve never heard of experienced performance artists striving to be authentic. They are trying to be real. I think awkwardness is much more interesting in terms of performance art. We could perhaps think in terms of central values in traditional performance art and the central values in traditional theatre. Then we have many overlapping forms and mixtures. Some performance artists use very theatrical tools in the sense of not being exaggerated. They dress up or use some sort of impersonation, for instance. But one of the core concerns in old-school performance art is that the action involves real time. So if it takes 20 minutes to do something, it takes 20 minutes, even if it’s very boring for the audience. In theatre, you would tell the story and jump to the conclusion or something like that.

The Body

Arlander: Another question, which is somehow central and always confusing for theatre people, is that it’s the artist’s body that’s in the foreground. So you can’t ask somebody else to make a performance. It’s you. You make the artwork. Of course, there are exceptions. (Marina Abramović being one example, when she was asking young artists to make remakes of her works and so on.) But in general, if you think of a, for instance, a painter who suddenly wants to make a performance, they’re usually very awkward, and they step in front of the audience and do something like a painting for them, they do it live in the moment and they share the process of the making of the painting.

Bryzgel: But isn’t that exactly how Allan Kaprow started? He moved from painting to performance…

Arlander: In a lot of the early works he made installations, spread painting into the room, rather than using his own body or doing it live. And then he made happenings, of course, which are not the same as performance art, but yeah…

Haakh: I just want to say one sentence to problematize the concept of authenticity, because in my experience, in the post-colonial times we’re living in, authenticity is often used as a criterion to assess the assumed closeness of somebody’s identity to how they are perceived by an audience. And this concept is usually used as a criterion for the non-white body more often than for white bodies etc. So I consider it a quite problematic concept and I’d like to suggest right now that we use the concept of improvisation instead in order to grasp the point that is being explored here. Improvisation is, of course, a common element in theatre and performance art and also other artistic practises. A recording of Joni Mitchell came to my mind to explain this. At one of her concerts, she was introducing a song and she took a moment to ground and centre herself before she can sing the song that she wrote and she just explained to the audience why she needs this moment. She said, to sing the song here is like to ask Vincent van Gogh to paint “The Starry Night” again in front of an audience.

(Photo: Art in Life)

Delegated performance

Orlová: It’s very refreshing to realise how we are thinking about certain things a bit differently. For example, Annette, you talked about performers using their own body only, but we’ve got delegated performance here. So it’s not possible to use it as a strong argument.

Arlander: But that’s the difference, can we have delegated performance art? We can outsource authenticity, as Bishop says, but can you really delegate performance art? Well, maybe you say we can, but I’m old-school. Perhaps we could distinguish between performance and performance art? But if somebody wants to call it delegated performance art, that’s fine. But if all kinds of performances made in an artistic context are performance art, then I also understand artists who then say, well, I don’t make performance art, I make action art. I suggest instead of thinking of terms that carry meaning, we could think about the artists as those who carry meanings or groups of artists or historical phenomena, rather than specific words. So, it’s difficult to find one word and agree on how that word should be used. That’s my point of view.

Maximilian Lehner: I very much like your thought of not narrowing it down to one exclusive definition. At the same time, I was surprised when you added that the body of the performer would be what ties together the idea of performance art…

Arlander: In traditional performance art it’s not the body of the performer, but rather the body of the artist, the body of the artist who’s not a performer.

Lehner: Thanks for the clarification. And what about the non-delegation of the performance? Couldn’t a concept be carried out by somebody else…

Old school

Arlander: I mean, in the old times the situation was different. And if we use the word perform, even electrons perform. So everything performs. Plants perform, trees perform. Of course, politicians perform and people perform other species, and so on. But I meant to make an example of classic old school performance art, which tried to differentiate itself from other types of performances. And that was by means of the artist’s, not the performer’s body, but the artist going in front of the audience. Instead of making a sculpture at home and then showing the sculpture they would enter the stage and become the sculpture, you understand? So this is historical. I’m not claiming that this is true to date, and we should stick to that. So sorry for confusing the debate.

Lehner: Okay, this was the misunderstanding. But even historically, I’d say, if you think of Merce Cunningham and John Cage’s performances: those were not their performances on stage. They were delegating it, even letting degrees of freedom to the performers on stage, mostly for creating their performances. So I thought about how we can even ask such questions about performance art in today’s visual art field. I think it leads to the point where we have to think further towards ideas of post-conceptualism and post-medium. To those practices which are always already transgressing their own boundaries to define themselves. I couldn’t think of any definitive criterion to mark out what’s performance art or what’s performance art in contrast to theatre. I just couldn’t imagine what dimension of those definitions would then apply because always, as soon as you look at theatre, you have an element of performance art that’s suddenly more interesting to the theatre maker, and vice versa. I’m really struggling to find anything.

Arlander: Well, Merce Cunningham and John Cage didn’t do performance art, they created experimental performances, but anyway. Maybe it’s the context that makes the difference. Maybe it’s the context. I remember a student of mine a long time ago who was making a performance with a thing that registers the EEG from the brain and he was a musician at the same time. But when he presented this in the black box studio in the Theatre Academy, the audience thought that it was a joke, an illusion, a representation. Nobody believed that it was a real technological device. And that was the force of the context, because in the theatrical context, it would have made sense to take it as a joke. In a performance art venue the audience would have expected it to be real. So maybe we can think about it in terms of context rather than in terms of what the performer does.

Theatre versus performance art / 2nd time

Lehner: I really like that idea. Again, there is the framework problem addressed by Nora earlier, which constantly reappears between my work environments as a researcher and as a producer for visual arts. On the side of the producer, I have to accept imprecise definitions: if you want theatre funding, you’re going to sell a performance as theatre and the other way around. Even theatres seem to accept performance art because they want to cross the boundaries of what they present. So suddenly, visual art performance is moving onto the theatre stage and thereby completely changing its nature. This is why I keep struggling with these definitions, even with the context argument which I consider to be very useful.

Orlová: I think it’s really important to think about it. It’s not appropriate anymore to say “well, performance art is something in-between”. Or to state we can’t define the genre because it will lose its power. If we’re working in this field, as producers or curators, historians or artists, we need to talk about it. Annette has contradicted herself a little, at one point she said that “all kinds of performances made in an artistic context are performance art” and then “Merce Cunningham and John Cage didn’t do performance art, they created experimental performances”. It´s also not just about the context. If you do theatre during performance art festival, it is still theatre.

Haakh: It now follows from our conversation, but I just thought that one thing relevant for performance has to do with putting something out of context. Which brings about this awkwardness, actually, and I think it is also navigating how different artistic fields function both as laboratories that encourage artistic development, but also as markets that function with different labels. For example taking a theatrical tool and putting it into a visual art space will change how it is perceived. And will invite different labels that will allow the artist and the artistic practice a different kind of mobility. And more mobility usually when it’s in a context that’s not so useful for certain tools.

Visual Performance

Łukasz Guzek: I’d like to introduce myself now and share my points of view. I’m a scholar working at the Academy of Fine Arts in Gdansk. I’m trying to transfer my knowledge to students-artists and let them use it for their art practice. We’ve also got education programmes in performance art and several artists graduated as performers from our academy. And I wrote a book about performance art in Poland, unfortunately it’s just in Polish. However, I’ve also written a few articles on this topic which are available in English, so you can learn about my viewpoints and methodology.

Referring to the beginning of our conversation about the notion of visual performance, it seems to me a very interesting proposition for researchers, because designations like performance art come into our languages as specific terms, different from the English linguistic practice in that they get adopted into our vocabulary as artistic terms. The terms “performance” appeared first in the field of visual art approximately at the end of seventies.

So for me, considering this term from the point of view of my research practice, visual performance is kind of tautology because performance art historically belongs to visual arts and it is a practice within the field of visual arts. And that’s something I think I can share with Jana, because we come from the same region and some things are similar in our experience, also in our political history. So for us it is obvious that performance art is part of the visual-art field. But there is a “but”. Since performance studies has originated, the term “performance” became broader and is still exanding. For many artists, everything could be performance. This has already been mentioned in this discussion. However we keep trying to open up this kind of practice to our art students. So as an art historian I’m aware of the historical conditions and as a teacher I’m pushing the boundaries, checking the limits of performance art.

Scholars like Carson or Schechner refer to the visual arts only marginally and randomly, usingperformance art as an umbrella term, in a very unspecific way and inaccurately, hence their disrespect to existing art historical discourse. And that’s why there’s a need for us now to discuss this topic again. That’s why this visual performance as a specific category of the discourse seems to me an interesting proposition for putting some order into terminology we use today studying performance art in light of performance studies. Such a clarification seems to be inevitable. We need to know the subject of our study. And how to build a research methodology.

Arlander: Okay, I have to interrupt here because I’m engaged in performance studies, and I think that’s a field completely separate from performance art. So there are two different things. And the idea that performance studies is only theatre is a misunderstanding. It’s seventies performance studies, which combined experimental theatre and anthropology (Schechner and Turner). In the nineties, performance studies was deeply influenced by Peggy Phelan and her interpretation of performances is very different. And I think today’s performance studies is focused not on theatre at all, or not even on performance art anymore, but on performance in an even broader sense, something like performing code or whatever. Performance studies is not of much help in the study of performance art. I think performance studies is a very interesting field and I think it’s important. But if you want to study performance art or action art or if you prefer visual performance, then performance studies can be confusing because its main interests lie outside art, not within art.

Guzek: Well, the term performativity is used very often today after Ericka Ficher-Lichte. This is a very useful proposal for describing the field of performance today. But it’s hard to apply it to the past, that is to art-historical studies on performance art. A visual performance categorization is interesting, as in the history of art performance art was always used as a genre crossing boundaries between painting, sculpture, film or theatre, sound or poetry, in the spirit of Fluxus. This ability is something we can use also in contemporary discussions about performance studies and about this performativity, in the broadest sense possible.

And as for delegated performance, this is also a kind of practice constantly connected with performance art as we’ve already mentioned Fluxus ideas and the concept of performance as a score. So this score can be licenced to other artists or can be given as a gift to perform such a score-action, “event score” as Alison Knowles has termed it. So the delegated performance is – an important word here – a conceptual practice everyone can use.

And also re-enactment practise that is something that comes from the idea of archiving performances and other conceptual and ephemeral practices. You have some evidence, some notes, some photos, scores or statements of artists from the past. And you can make a performance art piece using all these traces. These are today’s practises which belong to the broad field of performance studies. So that’s why I mean performativity and performance studies are very useful to study contemporary art pieces. However to enable deep research it should be more specific, for example to be categorized by concepts like visual performance.

Performances for Camera

Arlander: I’m thinking about that big confusion of the term performativity, which Barbara Bolt has written about, since you’ve mentioned Erika Fischer-Lichte. At a conference in 2008 she spoke of the actor’s performance , meaning the actors’ art of performing, and made everybody confused. But is this interesting for us now? I agree with everything you said about Fluxus, about scores, etc. But if I think of what would be interesting to discuss, from my perspective, it is the phrase “visual performance”, which I think can be quite controversial. Not perhaps in the visual art world where artists make performances, but in the traditional performance art world, which is a subculture. If we think of the literal meaning of the word, then “visual” is a quality of the performance, and it means a performance that is visual. But performance artists can make works that are more auditive than visual, focused on movement, etc. And if you think of visual performance in the sense of performance made by a visual artist, a visual artist’s performance, then you define the work by the maker. Some people think I make visual performance, because I perform for the camera, but audio-visual would be a better term. The question of performances for the camera, which have changed completely through the covid situation and the pandemic, is revealing. Because even many traditional performance artists or action artists, who earlier dismissed performances for camera, now wanted a live audience and an exchange between the performer and the audience…

Guzek: As to this practice, the performance for the camera, this is also a practice of the seventies conceptual art. So these post-pandemic or during pandemic performances are just contemporary examples. As for Erika Fischer-Lichte and theatre, she talks about Jerzy Grotowski’s unique piece of theatre, and there’s also an appretiation for his actors (Ryszard Cieslak) and arrangements on the stage, e.g. how the audiences sat very close to the actor so they could feel the smell the actor’s sweat. Fischer-Lichte uses this example of a theatre-piece to illustrate the nature of performativity, and the same goes for Tadeusz Kantor, who combined theatre and happenings which he called “happening theatre”. However he never took part in performance art festivals, he refused such participation despite being a member of the same group with Zbigniew Warpechowski. They were very close personally but in terms of art, the definition of what is happening, performance or theatre they were poles apart.

Distinctions between Theatre and Performance Art

Orlová: Researchers like Schechner come from a theatre background and, very simply put, they interpret every kind of performance as theatre. For sure, there’s certain development within the discipline, however the reference framework remains still the same.

At this point, I’d love to share with you the results of my research focusing on distinctions between theatre and performance art. I have read tons of different studies, researching theatre theory a lot, and performance studies as well. But you’ve already mentioned this is not really helpful. But anyway, in the Czech Republic, everything is mixed up a lot, for example focusing on performance studies when trying to understand performance art.

So in conclusion I’ve got, I hope, a pretty simple theory based on concept of illusiveness. There are different levels of illusion, for example an illusion of identity (in case you’re pretending you’re someone else) or an illusion of experience, environment or things that you use. We can pretend we’re on the beach right now and having a drink, etc. This whole concept is connected with preparation, rehearsals, and repeating. So from my point of view, the more the event is prepared in detail or as a whole, the closer it is to the theatre and vice versa. It works on a scale.

Sure, there are a lot of details I could talk about: fragmentary authenticity, the role of documentation and the position of the observer, which is different in theatre and visual performance. A really obvious one is different education: actors are trained in vocal and bodily expression while performance artists are not. Nevertheless, the concept of illusiveness can be used as a very simple tool to distinguish whether an art piece you are currently observing is visual performance or theatre.

It can be also said that the visual performance is a non-illusional and non-utilitarian human activity done in the context of conceptual art. This means the art piece is not illusive (so I’m not pretending anything), I’m not doing anything for a certain practical purpose and it’s within the context of conceptual art. The aim is not to make strict labels, this works on a scale: if there’s a lot of illusion in an art piece, it’s definitely closer to theatre.

Guzek: I think that what Jana has said about scaling as a definition method is very interesting, it’s a kind of performative scale with some points closer to or farther from performance to theatre areas. I think we need a new methodology for dealing with performance art in the face of performance studies achievements, we have a lot of literature for coping with this very complex issue. Jana, you’ve sent me a text where you talk about ritual, which is another interesting hypothesis, assuming all performances are ritualistic by nature, one way or another.

Orlová: Thank you for mentioning this. I assume all performances (including everyday life performances and art performances as well) have an inherent ritualistic aspect. Maybe this can be a theme for another meeting.

Arlander: It’s very difficult to take part in this discussion because you just briefly introduced it, but the question of illusion sounds as a good starting point. For me it seems related to the issue of representation versus presentation. In traditional theatre studies there’s the idea that something is represented on stage. The thing itself isn’t there, only a representation of it, the illusion of it, if you prefer that term. The spectator expects that the murder depicted on stage only represents a murder, and is not happening for real. Whereas in performance art the spectator often expects what’s there to be real. I uploaded onto the chat the manifesto by Marilyn Arsem, which I mentioned before. It doesn’t mean I agree with her in everything. I’ve spoken to her and she consciously exaggerated her statements since it’s written as a manifesto, as a provocation. But I find it very useful when you’ve got to understand conservative performance artists, because in some sense the traditional performance-art world is in fact very conservative. I remember times when people said the contemporary art world and performance art world are two very different worlds. Nowadays, it’s perhaps no longer so. Marilyn can be a good discussion partner for you.

Bryzgel: It’s just interesting for me as art historian and someone who came up through the discipline of art history and now works in a visual culture department. It’s only recently that I even learned about this discussion because I never really even knew that performance art was taught in theatre or performance studies departments. For me, it was always through the context of art history and I’ve never really had to even confronted that debate. I know there’s this tradition in the States with Richard Schechner et al., but it seems to from the people I know that much more in Europe and the UK, you’ll have performance art taught through theatre studies and theatre departments. Regardless, it’s not a debate that I’ve ever had to really engage with, because theatre is just another type of art. I was never really concerned with that definition.

Anyway, I think it’s interesting that you know that from the perspective of theatre studies, there’s that concern. I seems to me almost protective like or self-protective to define these different things. Performance art is well integrated into art history these days, but the specific debate about what is performance art versus what theatre or experimental theatre are, we never really touched that.

Arlander: Well, Amelia Jones has complained that art history never really takes into account the real bodies, only the documents of the actions. But if you think of Roselee Goldberg, she has been criticised very much because of her definition of performance art, which was that all a visual artist does is performance art. If a visual artist directs a ballet, it becomes performance art because it’s made by a visual artist: in some sense that’s a little weird. I think visual artists can make many kinds of performances.

Bryzgel: I agree. But she was the first person who really tried to define this thing from within the art-historical context.

Guzek: I’d like to add that in the Polish art history, in the seventies, under the influence of conceptual art, the difference between performance art and theatre was emphasised very strongly and so were the differences between performance art and visual arts. Performance art was in the field of the visual arts as it belonged to conceptual art. Conceptual artists and performance artists worked together. So insomuch as the conceptual art was part of the visual arts, so was performance. Well, this is the historical background. In the nineties, we tried to organise festivals with the participation of performance artists and some alternative theatre groups at the same time and it was disaster. They didn´t have any common ground. However much they loved each other, members of (not only professional) theatre groups thought: Look at this performance artist, totally amateur, what they’re doing on the stage. And performance artists said: Just look at them. They are drinking from empty glasses. So stupid.

Analyse the Performance Art

Lehner: I guess this would happen if you mixed up different kinds of performance art scenes too. Within, there are different foundations on how they conceptualise their own approaches. And how they’d deal with it. I’m teaching at contemporary art at an art history department and we are faced with the problem of how to teach performance and how to implement it within art history courses. Because there are so many different approaches. I mean, up to now, you still have those traditional Californian art scene performance artists who have this very serious approach to dealing with objects and words, which is completely in opposition to those very bodily and physical European artists. Even though they know each other’s style and would understand each other, they’d probably clash in how they interpret their styles. It might help not to even bother about defining performance, rather to think about how to analyse and describe performances. This is also what I am dealing with when teaching at an art history department. At the very beginning of the conversation, Annette referred to temporality in performance, which is my particular interest. To trace the temporal structures within works, it is often helpful to include theoretical frameworks from other disciplines into art historical research. It might be fruitful in a similar way, instead of remaining between performance, performance art, and theatre research, to connect these approaches in order to be able to better grasp performance art.

Orlová: In my experience, the international performance art scene is very unified. Even in Europe, there is still that serious approach and there are also artists who mix both approaches… and there is no problem with that. Again, the issue is what we mean by performance — that’s the point where I suppose misunderstandings and misinterpretations arise. As our debate has shown, if we want to talk about performance, we have to be able to describe it. And how do you want to describe and analyze performance (or anything else) without knowing what we are describing and analyzing? When we work as critics or curators, we need to be well aware of what is typical or unique to a given genre. For example, if we try to write about visual performance as we do with a poem or a piece of theater, it is possible, but evaluating performance, for example, in terms of verse arrangement or dramaturgy is not a functional approach, because performance does not work that way. However possible it is to draw some interdisciplinary methodological inspiration…

Lehner: I use methods from film studies to analyse video art. This idea introduced by some art historians seems quite obvious, but wasn’t really common in art history. If you combine different approaches, you suddenly understand decisions within a video work which come from other sources, from cinematic culture, TV, or YouTube, that were appropriated and might immediately be grasped by the audience identifying these references, at least in part. Implementing different theoretical frameworks helps us to put these sources as well as certain decisions on perspectives, editing, or sound in relation to each other and within a broader meaning of the work.

Arlander: That’s a good analogy between theatre and performance, which are somehow similar, superficially, but not the same. You can grab some things from another field and use it in your own way. But you can grab things from film as an artist who works with moving images, as you would say today, without making films (although some artists do that, too). For instance I’m mixing elements from performance art, environmental art and media art in my video works. In the same way some performance artists have used tools from the theatre or dance. And visual artists have used choreographic tools when they direct performances with professional performers or laymen in art galleries. Such performances created by artists in museums and the performance art that takes place within the performance art subcultures can be worlds apart.

Orlová: Thank you all very much! We have broached many interesting topics here; inspiring ideas have been expressed. It would be great if we could stay in touch and continue our discussion… Through the revue Dance Zone or somewhere else.

Jana Orlová — a theorist, performer and poet. Her simultaneous theoretical and artistic background allows her to work as a curator and critic. At the end of 2021 she received her Ph.D. from the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague (Department of Theory). Her poetry has been translated into many languages, including Hindi and Chinese, and she has participated in numerous art events across Europe. Her research focuses on performance art and borderline art forms.

Annette Arlander (1956)- an artist, researcher and a pedagogue, one of the pioneers of Finnish performance art and a trailblazer of artistic research. In 2018 – 2019 she was professor of performance, art and theory at Stockholm University of the Arts with the Performing with Plants artistic research project. She was also the principal investigator of the Academy of Finland funded research project titled, How to Do Things with Performance (2016 – 2020). At present she is visiting researcher at Academy of Fine Arts, University of the Arts Helsinki with the project, Meetings with Remarkable and Unremarkable Trees. Her research interests include artistic research, performance-as-research and the environment. Her artwork moves between the traditions of performance art, video art and environmental art.

Amy Bryzgel — Chair in Film and Visual Culture at the University of Aberdeen, where she has worked since 2009. She is the author of three books: Performing the East: Performance Art in Russia, Latvia and Poland (IB Tauris, 2012); Miervaldis Polis (Riga, Latvia: Neputns, 2015) and Performance Art in Eastern Europe since 1960 (Manchester University Press, 2017). She has received numerous grants for her research, including a Leverhulme Fellowship and an Arts and Humanities Research Council Early Career Fellowship.

Łukasz Guzek (1962) — professor of the Academy of Fine Arts in Gdansk.In his work he combines scientific research in art history with art criticism and curatorial practice.His research interests include the art of the twentieth century, particularly the art of the seventies, including conceptual art, performance art, installation art, breakthrough modernism / postmodernism in the visual arts, as well as documentation of art, understood both as a problem of the theory of art and as the practice of archiving, retention, maintenance and care of works of contemporary ephemeral art forms. Research conducted recently is linked with the area of performance studies. The currently implemented research project concerns the study of contemporary art in Middle Europe. Since 2009 he has been an editor-in-chief of scholarly journal Art and Documentation (www.journal.doc.art.pl). He published three books in Polish: Installation Art. The Question of Relationship Between Space and Presentness in Contemporary Art (2007), Performatization of Art. Performance Art and Action Factor in Polish Art Criticism (2013) and Reconstruction of Action Art in Poland (2017),

Nora Haakh (1985) — cultural scientist and performing artist between theatre and the visual arts. She earned her PhD in 2020 at the Freie Universität Berlin with her dissertation entitled “Layla und Majnun in the Contact Zone” on the questions of transfer and translation from Arabic to German in contemporary theatre, which was awarded a special price in the frame of the “Augsburg Award for Intercultural Studies”. She has been working as a dramaturge with many translocal artists and directed contemporary Arabic Drama. Currently, she teaches at the HAW Hamburg and Cours Florent Berlin and works as a Graphic Recorder, experimenting with the possibilities of Live Drawing and Generative Scribing such as performative storytelling tools, working with artist collectives like the Social/Artistic Laboratory AUCH, Berlin, or “Frauen am Fluss”, Munich. Her current artistic research focuses on interspecies relations and is called “Tree Translator”. www.nora-haakh.de

Maximilian Lehner – teacher, co-founder of The Real Office in Stuttgart. He studied art theory and philosophy in Paris, Stuttgart, and Linz and has participated in curatorial courses at Salzburg Summer Academy and ECCA Cluj/Timisoara Art Encounters. He has curated exhibitions for ElectroPutere (RO), Škuc Gallery (SI), or Fünfzigzwanzig (AT), and written texts for BLOK, Kajet, Revista Arta, and numerous academic publications. In recent time he pursues PhD studies at the Institute of Contemporary Arts and Media at KU Linz.